Compare and Contrast Their Art Bearden Lawrence Basquiat or Colescott

African-American art is a broad term describing visual fine art created by Americans who also place every bit Black. The range of art they have created, and are standing to create, over more than ii centuries is as varied as the artists themselves.[one] Some have fatigued on cultural traditions in Africa, and other parts of the earth, for inspiration. Others take found inspiration in traditional African-American plastic art forms, including handbasket weaving, pottery, quilting, woodcarving and painting, all of which are sometimes classified as "handicrafts" or "Folk Fine art."[two] [iii]

Many have too been inspired by European traditions in art, every bit well as personal experience of life, piece of work and studies there.[iv] [five] [vi] Like their western colleagues, many work in Realist, Modernist and Conceptual styles, and all the variations in between, including America'southward dwelling-grown Abstract expressionist move, an approach to art seen in the work of Howardena Pindell, McArthur Binion and Norman Lewis, amidst others.[seven]

Like their peers, African-American artists also work in an array of media, including painting, print-making, collage, assemblage, drawing, sculpture and more.[8] Their themes are similarly varied, although many likewise address, or feel they must accost, issues of American Blackness.[9] [10]

In one case known as the "sculptor of horrors," Meta Vaux Warrick Fuller favored a mix of Conceptual Realism and Symbolism, and took inspiration from ghost stories.[11] Mentored by Henry Osawa Tanner, critiqued by Auguste Rodin, and exhibited in the 1903 Salon,[11] [12] she recognized that a continued career relied on "meet[ing] requests for race-based work from the leading Black scholars, activists, and luminaries who controlled the commission pipeline."[13] By accepting that reality, W.Eastward.B. Du Bois became i of her patrons, and she became the first African-American woman recipient of a federal commission ... for progress-themed dioramas for Jamestown'south tercentennial ... and, after, for the fiftieth anniversary commemoration of the Emancipation Proclamation," just information technology all came at some cost.[xi] [12] [13]

Some other extreme is illustrated by an artist similar Emory Douglas, the old Minister of Civilisation for the Black Panther Party, whose art was consciously radical, and has since go iconic.[14] "[C]redited with popularising the term 'pigs' for corrupt police force officers," his best-known imagery was frequently harshly critical of the existing power structure, openly violent and, like all political iconography, intended to persuade.[14] [xv]

Edmonia Lewis was deputed to do President Grant's portrait, ca.1870.

Meta Vaux Warrick Fuller was Rodin'southward protegee, 1910.

Sculptor Edmonia Lewis, by contrast, financed her showtime trip to Europe in 1865 by selling sculptures of abolitionist John Brown and Robert Gould Shaw, the Union Colonel who led the enlisted black 54th Massachusetts Infantry Regiment during the Civil War.[16] She would later on incorporate issues of race more subtly, using modernistic themes and aboriginal symbols in Neoclassical sculpture to suggestive ends.[5] In response to a bust Lewis had made of her, her patron Anna Quincey Waterston wrote admiringly of her: Tis fitting that a daughter of the race / Whose chains are breaking should receive a gift / So rare as genius.[xvi]

The grandchild of slaves, print artist and sculptor Elizabeth Catlett was also an activist. Although some of her art includes confrontational symbols from the Black Ability movement, she is all-time-known for her portrayals of African-American heroes: MLK, Malcolm X, Harriet Tubman — and strong maternal women.[17] [18] [nineteen] Sculptor Augusta Vicious's work was similarly uplifting. In a large commission for the 1939 New York Earth's Fair, "Lift Every Voice and Sing", which is often described as the Black National Anthem, inspired a chosen Elevator Every Voice and Sing, besides known every bit The Harp as it depicted black singers as the strings of the instrument.[6]

Painter Organized religion Ringgold, who is known for her politicized fine art, has been described as having a "gorgeous gut dial."[20] Her The American People Series #20: Die which depicts a bloody clash between Cubist black and white figures, was hung contrary Pablo Picasso's Les Demoiselles d'Avignon in the newly renovated MOMA in 2019, the improve to start a conversation betwixt the "savage strength" of their respective compositions.[twenty] [21] [22] Conceptual creative person Fred Wilson focuses on other kinds of composition, "juxtaposing wildly anomalous items, such as a slave statue and a set up of fine communist china." A 1999 MacArthur "genius grant" recipient, his work encourages "unpacking and upending assumptions nigh race and history surrounding each."[23] [24]

Narrative artists like Jacob Lawrence employ history painting to tell a story in images, every bit his ain Migration Series shows. The threescore-panel ballsy depicts the relocation of a million African Americans to the industrialized North after World War II.[8] [25] As in the cases of Kehinde Wiley[ citation needed ] and Amy Sherald,[26] history painting tin can also involve portraiture; in this instance, the official portraits of Barack and Michelle Obama, respectively.

Artists similar Horace Pippen and Romare Bearden chose more ordinary subject matter, relying on contemporary life to inspire uncontroversial imagery. The influential Henry Tanner did, too, in paintings like The Banjo Lesson and the Thankful Poor[4] although those paintings — like many of his landscapes and Biblical scenes — often seem illuminated from within. The showtime African-American to enroll in the prestigious Pennsylvania Academy of the Fine Arts in 1880, Tanner studied with Realist painter Thomas Eakens.[iv] He went on to become the showtime African-American artist to earn international acclaim. He was elected to the National University of Design in 1910 and designated an honorary chevalier of the Lodge of the Legion of Honor in 1923.[27]

Early on African-American art [edit]

Pre-colonial, Antebellum and Civil State of war eras [edit]

Engraving of a chained female slave by Patrick H. Reason, 1835. Oft circulated with the caption "Am I non a adult female and a sister?"

The earliest prove of African-American art in the United States is the work of skilled craftsmen slaves from New England. 2 categories of slave arts and crafts items survive from colonial America: articles that were created for personal use by slaves and articles created for public use. Examples from the period between the 17th century and the early 19th century include: pocket-size drums, quilts, wrought-iron figures, baskets, ceramic vessels, and gravestones.[28] [29]

Many of Africa's well-nigh skilled slave artisans were hired out by slave owners. With the consent of their masters, some slave artisans were also able to go on a pocket-sized percent of the wages earned in their spare fourth dimension to save enough money to purchase their liberty, and that of their family members.[xxx]

The public works of art produced by slave craftsmen were an important contribution to the Colonial economy. In New England and the Mid-Atlantic colonies, slaves were apprenticed every bit goldsmiths, cabinetmakers, engravers, carvers, portrait painters, carpenters, masons and iron workers. The construction and decoration of the Janson House, built on the Hudson River in 1712, was the work of African-Americans. Many of the oldest buildings in Louisiana, South Carolina and Georgia were built past craftsmen slaves.[29]

In the mid-eighteenth century, John Bush was a powder horn carver and soldier with the Massachusetts militia fighting with the British in the French and Indian War.[31] [32] Patrick H. Reason, Joshua Johnson, and Scipio Moorhead were amongst the earliest known portrait artists, from the period of 1773–1887. Patronage by some white families allowed for private tutoring in special cases. Many of these sponsoring whites were abolitionists. The artists received more encouragement and were better able to support themselves in cities, of which in that location were more in the North and edge states.

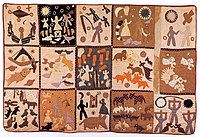

Harriet Powers (1837–1910) was an African-American folk creative person and quilt maker from rural Georgia, U.s., born into slavery. Now nationally recognized for her quilts, she used traditional appliqué techniques to record local legends, Bible stories and astronomical events on her quilts. Only two of her late quilts have survived: Bible Quilt 1886 and Bible Quilt 1898. Her quilts are considered amongst the finest examples of 19th-century Southern quilting.[33] [34]

Similar Powers, the women of Gee's Bend developed a distinctive, bold and sophisticated quilting style based on traditional American (and African-American) quilts, merely with a geometric simplicity. Although widely separated by geography, they have qualities reminiscent of Amish quilts and Modern art. The women of Gee's Bend passed their skills and aesthetic downwards through at least half dozen generations to the present.[35] At in one case, scholars believed slaves sometimes used quilt blocks to alarm other slaves to escape plans during the fourth dimension of the Secret Railroad,[36] but near historians exercise not agree. Quilting remains live every bit form of creative expression in the African-American community.

Reconstruction [edit]

After the Ceremonious War, information technology became increasingly acceptable for African American-created works to exist exhibited in museums, and painters and sculptors increasingly produced works for this purpose.[37] These were works mostly in the European Romantic and Classical traditions of landscapes and portraits. Edward Mitchell Bannister, Henry Ossawa Tanner and Edmonia Lewis are the most notable from this period. Others include Meta Vaux Warrick Fuller, a female artist who, like Edmonia Lewis, was a sculptor, as well every bit Grafton Tyler Dark-brown and Nelson A. Primus.[13] [11] [38]

The goal of widespread recognition beyond racial boundaries was first eased inside America'south big cities, including Philadelphia, Boston, Chicago, New York, and New Orleans. Even in these places, nevertheless, there were discriminatory limitations. Abroad, yet, African Americans were much better received. In Europe — especially Paris, France — these artists were freer to experiment with techniques outside traditional western art. Liberty of expression was much more prevalent in Paris and, to a bottom extent, Munich and Rome.[ citation needed ]

Gimmicky art [edit]

Self Portrait, 1920

Self-Portrait, 1933

Jacob Lawrence gained recognition at age 23 for his 60-console "The Migration Serial," depicting the Great Migration of African Americans from the rural South to the urban North. The name of this panel is "Douglass argued against poor Negroes leaving the S"

Portrait of Jacob Lawrence, 1941.

The Harlem Renaissance [edit]

The Harlem Renaissance refers to an enormous flourishing in African-American fine art of all kinds, including visual art. Ideas that were already widespread in other parts of the world at the fourth dimension had begun to spread into U.S. artistic communities during the 1920s. Notable artists in this flow included Richmond Barthé, Aaron Douglas, Lawrence Harris, Palmer Hayden, William H. Johnson, Sargent Johnson, John T. Biggers, Earle Wilton Richardson, Malvin Gray Johnson, Archibald Motley, Augusta Savage, Unhurt Woodruff and photographer James Van Der Zee.[ commendation needed ]

William E. Harmon, an art patron and addict, established the Harmon Foundation in 1922, and it served as a large-scale patron of African-American art until 1967, generating interest in, and recognition for, artists who might have otherwise remained unknown. The Harmon Award and the annual "Exhibition of the Work of Negro Artists" further contributed to the support, as did the William E. Harmon Foundation Award for Distinguished Accomplishment Among Negroes, which although non express to visual artists was awarded to several of them, including Hale Woodruff, Palmer Hayden and Archibald Motley. In 1929, the funding temporarily concluded as a result of the Swell Depression, but to resume mounting exhibitions and offering funding one time the economy revived artists like Jacob Lawrence, Laura Wheeler Waring and others.

Past 1933, the U.South. Treasury Section'southward Public Works of Fine art Project was attempting to provide support for artists in 1933, but their efforts proved ineffective. President Franklin D. Roosevelt created the Works Progress Administration (WPA) in 1935, and that program succeeded at providing all American artists, and peculiarly African-American artists, with a means to earn a living in a devastated economy. By the middle of the 1930s, more than 250,000 African Americans were involved with the WPA,[39] including Jacob Lawrence, Gwendolyn Knight, sculptor William Artis; painter and children's book illustrator Ernest Crichlow, cartoonist and illustrator Elton C. Fax, photographer Marvin Smith, Dox Thrash, who invented the printmaking method carborundum Mezzotint, painters Georgette Seabrooke and Elba Lightfoot, best known for their Harlem Hospital murals; Chicago printmaker Eldzier Cortor; and renowned Illinois-based artist Adrian Troy and many others.[39] Many of these artists constitute themselves drawn to the interwar movement known every bit Social Realism, which reflected the politics and socioeconomic views of a generation that had been drafted into WWI, merely to trip the light fantastic through the Roaring 1920s and crash in the Great Depression.

Important cities with significant black populations and important African-American art circles included Philadelphia, Boston, San Francisco and Washington, D.C. The WPA led to a new wave of important blackness art professors. Mixed media, abstract art, cubism, and social realism became not but acceptable, but desirable. Artists of the WPA united to form the 1935 Harlem Artists Social club, which developed community art facilities in major cities. Leading forms of fine art included drawing, sculpture, printmaking, painting, pottery, quilting, weaving and photography. In 1939, however, the costly WPA and its projects all were terminated.[ commendation needed ] In 1943, James A. Porter, a professor in the Department of Fine art at Howard University, wrote the first major text on African-American art and artists, Modern Negro Fine art.[ commendation needed ]

Mid-Century [edit]

Sunday Forenoon Breakfast past Horace Pippin, 1943.

Romare Bearden, "After Church," northward.d.

In the 1950s and 1960s, few African-American artists were widely known or accepted. Despite this, The Highwaymen, a loose clan of 26 African-American artists from Fort Pierce, Florida, created idyllic, speedily realized images of the Florida landscape and peddled some 200,000 of them from the trunks of their cars. In the 1950s and 1960s, it was impossible to find galleries interested in selling artworks by a grouping of unknown, self-taught African Americans,[40] and then they sold their art directly to the public rather than through galleries and art agents. Rediscovered in the mid-1990s, they are recognized today equally an important part of American folk history,[41] [42] and the current market price for an original Highwaymen painting can easily bring in thousands of dollars. In 2004, the original group of 26 were inducted into the Florida Artists Hall of Fame.[43] Currently eight of the 26 are deceased, including A. Hair, H. Newton, Ellis and George Buckner, A. Moran, L. Roberts, Hezekiah Bakery and, most recently, Johnny Daniels. The full listing of 26 tin can be institute in the Florida Artists Hall of Fame, as well as diverse highwaymen and Florida fine art websites.

Subsequently the 2d Earth War, some artists took a global approach, working and exhibiting abroad, in Paris, and equally the decade wore on, relocated gradually in other welcoming cities such as Copenhagen, Amsterdam, and Stockholm: Barbara Chase-Riboud, Edward Clark, Harvey Cropper, Beauford Delaney, Herbert Gentry,[44] Bill Hutson, Clifford Jackson,[45] Sam Middleton,[46] Larry Potter, Haywood Bill Rivers, Merton Simpson, and Walter Williams.[47] [48]

Some African-American artists did make it into important New York galleries by the 1950s and 1960s: Horace Pippin, Romare Bearden, Jacob Lawrence, William T. Williams, Norman Lewis, Thomas Sills,[49] and Sam Gilliam were amid the few who had successfully been received in a gallery setting. The Ceremonious Rights Movement of the 1960s and 1970s led artists to capture and express the irresolute times. Galleries and community art centers developed for the purpose of displaying African-American art, and collegiate teaching positions were created by and for African-American artists. Some African-American women were also agile in the feminist art movement in the 1970s. Faith Ringgold made work that featured black female subjects and that addressed the conjunction of racism and sexism in the U.S., while the commonage Where We At (WWA) held exhibitions exclusively featuring the artwork of African-American women.[50]

Past the 1980s and 1990s, hip-hop graffiti began to predominate in urban communities. Most major cities had developed museums devoted to African-American artists. The National Endowment for the Arts provided increasing support for these artists.

Belatedly 20th/early 21st century [edit]

Kara Walker, a contemporary American artist, is known for her exploration of race, gender, sexuality, violence and identity in her artworks. Walker's silhouette images work to span unfinished folklore in the Antebellum Due south and are reminiscent of the before piece of work of Harriet Powers. Her nightmarish still fantastical images incorporate a cinematic experience. In 2007, Walker was listed among Fourth dimension Magazine'south "100 Almost Influential People in The World, Artists and Entertainers".[51] Textile artists are role of African-American art history. According to the 2010 Quilting in America industry survey, there are 1.vi one thousand thousand quilters in the Us.[52] One historic non profit organization with several members who are quilters and fiber artists is Women of Visions, Inc. located in Pittsburgh, Pennsylvania at the Pittsburgh Center for the Arts. WOV Inc artists past and nowadays work in a diverseness of mediums. Those who have shown internationally include Renee Stout and Tina Williams Brewer.

Influential contemporary artists include Larry D. Alexander, Laylah Ali, Amalia Amaki, Emma Amos, Jean-Michel Basquiat, Dawoud Bey, Camille Billops, Mark Bradford, Edward Clark, Willie Cole, Robert Colescott, Louis Delsarte, David Driskell, Leonardo Drew, Mel Edwards, Ricardo Francis, Charles Gaines, Ellen Gallagher, Herbert Gentry, Sam Gilliam, David Hammons, Jerry Harris, Joseph Holston, Richard Hunt, Martha Jackson-Jarvis, Katie S. Mallory, Thousand. Scott Johnson, Rashid Johnson, Joe Lewis, Glenn Ligon, James Footling, Edward L. Loper Sr., Alvin D. Loving, Kerry James Marshall, Eugene J. Martin, Richard Mayhew, Sam Middleton, Howard McCalebb, Charles McGill, Thaddeus Mosley, Sana Musasama, Senga Nengudi, Joe Overstreet, Martin Puryear, Adrian Piper, Howardena Pindell, Faith Ringgold, Gale Fulton Ross, Alison Saar, Betye Saar, John Solomon Sandridge, Raymond Saunders, John T. Scott, Joyce Scott, Gary Simmons, Lorna Simpson, Renee Stout, Kara Walker, Carrie Mae Weems, Stanley Whitney, William T. Williams, Jack Whitten, Fred Wilson, Richard Wyatt Jr., Richard Yarde, and Purvis Young, Kehinde Wiley, Mickalene Thomas, Barkley Hendricks, Jeff Sonhouse, William Walker, Ellsworth Ausby, Che Baraka, Emmett Wigglesworth, Otto Neals, Dindga McCannon, Terry Dixon (creative person), Frederick J. Brownish, and many others.[ citation needed ]

Galleries [edit]

The Art [edit]

Early African-American [edit]

(Option was limited by availability.)

-

Painter Edward Mitchell Bannister, "Pleasant Pastures," 1887.

-

Painter Grafton Tyler Brown, "Former Faithful Geyser, Yellowstone National Park," 1887.

-

Sculptor Edmonia Lewis, "Old Arrow Maker," 1872.

-

Painter Henry Ossawa Tanner, "The Proclamation," 1898.

Harlem Renaissance [edit]

(Selection was limited past availability.)

-

Self-portrait by painter Malvin Gray Johnson, 1934.

-

Photo past the painter William H. Johnson, 1931.

-

Lensman James Van Der Zee'southward photo of a woman in evening attire, 1922.

-

William H. Johnson's "Three Friends," ca. 1945.

-

Archibald Motley, "Gettin' Religion," 1948.

-

Meta Vaux Warrick Fuller's "Ethiopia Awakening,"1921.

-

Laura Wheeler'southward "Heirlooms," 1916.

Contemporary [edit]

(Pick was limited by availability.)

-

Larry D. Alexander, "Send in the Clown", 2007.

-

Sam Gilliam 's "Jamaica Center Station Riders, Blue", 1991.

-

Adrian Piper 'southward "Alice Down the Rabbit Pigsty", 1965.

-

Howardeena Pindell'southward "Queens, Festival", 2007.

-

MacArthur Accolade-winning artist Fred Wilson 'south book A Critical Reader, 2011.

The Artists [edit]

Harlem Renaissance [edit]

(Selection was limited by availability.)

-

Painter, sculptor, illustrator and muralist Charles Alston in 1939.

-

Sculptor and character artist Henry W. Bannarn in 1937.

-

Sculptor Richmond Barthé working on a clay figure, n.d.

-

Artist Romare Bearden, photographed in his war machine uniform in 1944.

-

Sculptor Leslie Bolling carving a sculpture, north.d.

-

Modernist painter Beauford Delaney in 1952.

-

Painter and illustrator Aaron Douglas, n.d.

-

Painter Palmer Hayden working on a landscape, n.d.

-

Creative person Sargent Johnson, assessing his own sculpture, due north.d.

-

Artist Loïs Mailou Jones in 1936.

-

Sculptor Augusta Savage, photographed between 1935 and 1947.

-

Painter Hale Woodruff at piece of work on a canvas, ca. 1936.

Contemporary [edit]

(Option was limited past availability.)

-

Painter and collagist Mark Bradford in 2016.

-

Artist Leonardo Drew in Brooklyn studio in 2012.

-

Creative person, scholar and curator David C. Driskell in 2016.

-

Sculptor and collagist Jerry Harris in 2008.

-

Painter, collagist and draftsman Eugene J. Martin in 1990.

-

Painter, printmaker and sculptor Gale Fulton March in 2020

-

Artists Sana Musasama and Janet Olivia Henry in 2019.

-

Painter and mixed media creative person Howardena Pindell in 2019.

-

Conceptual creative person Adrian Piper in 2005.

-

Painter and mixed media sculptor Faith Ringgold in 2017.

-

Assemblage artist Betye Saar in 2017.

-

Multimedia painter Raymond Saunders in 1995.

-

Photographer and multimedia artist Lorna Simpson in 2009.

Collections of African-American fine art [edit]

Many American museums hold works by African-American artists, including Smithsonian American Fine art Museum[53] Colleges and universities with important collections include Fisk University, Spelman College and Howard University.[54] Other important collections of African-American art include the Walter O. Evans Collection of African American Art, the Paul R. Jones collections at the Academy of Delaware and Academy of Alabama, the David C. Driskell Art collection, the Harmon and Harriet Kelley Drove of African American Art, the Schomburg Heart for Research in Black Culture, the Studio Museum in Harlem and the Mott-Warsh collection.

See also [edit]

- African-American culture

- African-American literature

- African-American music

- Black Arts Movement

- Black Art: In the Absence of Light

- Chicano art

- Gullah/Geechee Cultural Heritage Corridor

- The Highwaymen (landscape artists)

- James A. Porter Colloquium on African American Fine art

- List of African-American visual artists

- Visual art of the United States

References [edit]

- ^ "Art by African Americans | Highlights | Smithsonian American Art Museum". americanart.si.edu . Retrieved 2021-02-23 .

- ^ Langford, Ellison (2019-12-sixteen). "Finding the thread: The tradition of African-American quilting". Scalawag . Retrieved 2021-02-23 .

- ^ "Crafts and Slave Handicrafts: An Overview | Encyclopedia.com". www.encyclopedia.com . Retrieved 2021-02-23 .

- ^ a b c "Henry Ossawa Tanner". Biography . Retrieved 2021-02-23 .

- ^ a b Alexandra Kiely (2020-02-thirteen). "The Fabulous Sculpture and Mysterious Life of Edmonia Lewis". DailyArtMagazine.com - Fine art History Stories . Retrieved 2021-02-24 .

- ^ a b Blain, Keisha N. (2017-03-03). "The nigh important black woman sculptor of the 20th century deserves more recognition". Medium . Retrieved 2021-02-24 .

- ^ O'Grady, Megan (2021-02-12). "Once Overlooked, Blackness Abstract Painters Are Finally Given Their Due". The New York Times. ISSN 0362-4331. Retrieved 2021-02-23 .

- ^ a b Stidhum, Tonja Renée. "On The 25th Anniversary Of His Expiry, We Call up And Honor Iconic Tennis Role player Arthur Ashe - Blavity". Blavity News & Politics . Retrieved 2021-02-23 .

- ^ Smith, Melissa (Apr 29, 2019). "Young Black Artists Are More in Need Than Always—But the Fine art World Is Burning Them Out". ArtNet.

- ^ "The Miseducation of the Blackness Artist". The Pioneer . Retrieved 2021-02-25 .

- ^ a b c d Davidson and P. Biddle, Benjamin. "The Sculpture of Meta Vaux Warrick Fuller" (PDF). The Magazine Antiques (September/October 2020): 34–40.

- ^ a b M. S.Ed, Secondary Educational activity; Thousand. F.A., Artistic Writing; B. A., English. "How is Meta Vaux Warrick Fuller'south "Ethiopia Awakening" a symbol of the Harlem Renaissance?". ThoughtCo . Retrieved 2021-02-25 .

- ^ a b c "The Meta Vaux Warrick Fuller Collection – Danforth". danforth.framingham.edu . Retrieved 2021-02-25 .

- ^ a b "The revolutionary fine art of Emory Douglas, Black Panther". The Guardian. 2008-10-27. ISSN 0261-3077. Retrieved 2021-02-24 .

- ^ "Fight the power: Alex Rayner meets the old Black Panthers' government minister of culture". The Guardian. 2008-10-24. Retrieved 2021-02-24 .

- ^ a b "Edmonia Lewis - Smithsonian American Art Museum". Google Arts & Civilisation . Retrieved 2021-02-24 .

- ^ "Elizabeth Catlett | Artist Profile". NMWA . Retrieved 2021-02-24 .

- ^ Rosenberg, Karen (2012-04-04). "Elizabeth Catlett, Sculptor With Eye on Social Issues, Is Dead at 96 (Published 2012)". The New York Times. ISSN 0362-4331. Retrieved 2021-02-24 .

- ^ "Blackness, Female person And An Inspirational Modern Artist". NPR.org . Retrieved 2021-02-24 .

- ^ a b Morris, Bob (2020-06-11). "Religion Ringgold Will Keep Fighting Back". The New York Times. ISSN 0362-4331. Retrieved 2021-02-23 .

- ^ Farago, Jason (2019-ten-03). "The New MoMA Is Here. Get Ready for Change. (Published 2019)". The New York Times. ISSN 0362-4331. Retrieved 2021-02-23 .

- ^ Weschler, Lawrence (31 January 2017). "Destroy this mad brute": The African root of World War I. ISBN9781632867186.

- ^ Chung, Evan (September 26, 2019). "Fred Wilson uses the museum every bit his palette". The World from PRI (Radio). Retrieved 2021-02-23 .

- ^ "Pace Chelsea Reopens With Fred Wilson'south 'Chandeliers'". SURFACE. 2019-09-12. Retrieved 2021-02-23 .

- ^ "Introduction | Jacob Lawrence: The Migration Serial". lawrencemigration.phillipscollection.org . Retrieved 2021-02-23 .

- ^ Fikes, Robert (2018-11-25). "Amy Sherald (1973- ) •". Retrieved 2021-02-23 .

- ^ "Henry Ossawa Tanner | American painter". Encyclopedia Britannica . Retrieved 2021-02-23 .

- ^ Sharon F. Patton, African-American Art, Oxford Academy Press, 1998.

- ^ a b Lewis, Samella (2003). African American Art and Artists. University of California Press.

- ^ Romare Bearden, Harry Henderson, A History of African-American Artists. From 1792 to the Present. New York: Pantheon Books, 1993.

- ^ USA Today Magazine. May 2005, Vol. 133 Issue 2720, pp. 48–52. 5p.

- ^ "The Great Warpaths".

- ^ Kyra East. Hicks (2009), This I Accomplish: Harriet Powers' Bible Quilt and Other Pieces.

- ^ Harriet Powers Archived 2007-ten-18 at the Wayback Machine, Early Women Masters

- ^ The Quilts of Gees Bend.

- ^ Raymond Dobard Jr., Ph.D., and Jacqueline Tobin, Hidden in Plain View, 1999.[ where? ]

- ^ "Host Europe GmbH – www.widewalls.ch". world wide web.widewalls.ch . Retrieved 2020-11-xviii .

- ^ George, Alice. "Sculptor Edmonia Lewis Shattered Gender and Race Expectations in 19th-Century America". Smithsonian Magazine . Retrieved 2021-02-25 .

- ^ a b "Artists of the New Deal". HISTORY . Retrieved 2021-02-24 .

- ^ Painting Florida Archived November eight, 2006, at the Wayback Machine

- ^ The Highwaymen Archived 2007-ten-18 at the Wayback Machine By Ken Hall.

- ^ Updates & Snapshots 2006 Archived March xi, 2008, at the Wayback Car

- ^ The Florida Highwaymen

- ^ Bearden. R., in An Bounding main Apart: American Artists Abroad. New York: Studio Museum in Harlem.

- ^ Malone, Fifty., in An Ocean Apart: American Artists Abroad. New York: Studio Museum in Harlem.

- ^ Williams, J. A., in An Bounding main Apart: American Artists Away. New York: Studio Museum in Harlem.

- ^ Driskell, David C., in An Ocean Apart: American Artists Abroad. New York: Studio Museum in Harlem.

- ^ Mercer, Valerie (1996), Explorations in the City of Light. New York: The Studio Museum in Harlem.

- ^ I. C. Thousand., (1957), "The Surprise of Painter Tom Sills," The Hamlet Phonation, p. 17.

- ^ Brown, Kay (2011). "The Emergence of Black Women Artists: The Founding of 'Where We Ar'". Nka: Journal of Contemporary African Art. 2011 (29): 118–127. doi:10.1215/10757163-1496399. S2CID 194127365.

- ^ Kruger, Barbara (2007)"Kara Walker", Time online. Retrieved 26 July 2007.

- ^ Kyra E. Hicks (2010), 1.vi One thousand thousand African American Quilters: Survey, Sites, and a Half-Dozen Art Quilt Blocks.

- ^ "Smithsonian American Art Museum and Renwick Gallery". americanart.si.edu . Retrieved 2020-04-04 .

- ^ "Museum of Fine Art | Spelman College". www.spelman.edu . Retrieved 2020-04-04 .

Sources [edit]

- Romare Bearden, Harry Henderson, A History of African-American Artists. From 1792 to the Present, New York: Pantheon Books, 1993.

- Driskell, David C. (2001), The Other Side of Color: African American Art in the Collection of Camille O. and William H. Cosby Jr. Pomegranate. ISBN 978-0-7649-1455-3

- Sylvester, Melvin R. African Americans in Visual Arts: A Historical Perspective. Long Isle University. Retrieved January 23, 2005.

- Perry, Regenia A. (1972). Selections of nineteenth-century Afro-American art. New York: The Metropolitan Museum of Art.

External links [edit]

- Secretarial assistant of State Glenda E. Hood Announces 2004 Hall of Fame Inductees

- Promoting Natural Florida Through the Arts

- Blog Almost African American Artists, Photographers, Galleries & Museums

- Jake Adam York, "Medicine equally Memory: Radcliffe Bailey at Atlanta's Loftier Museum of Art", Southern Spaces, January 26, 2012.

Source: https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/African-American_art

0 Response to "Compare and Contrast Their Art Bearden Lawrence Basquiat or Colescott"

Post a Comment